Recent Actions by the Walt Disney Company are the Latest Sign that Financialization and Market Concentration have Put US Business Dynamism in Jeopardy

Key terms: financialization, innovation, market concentration

Note: The following article comprises my own views and does not reflect those of my employer. Any analysis is unrelated to the work I do at my job. I promise I tried my hardest to make this piece shorter.

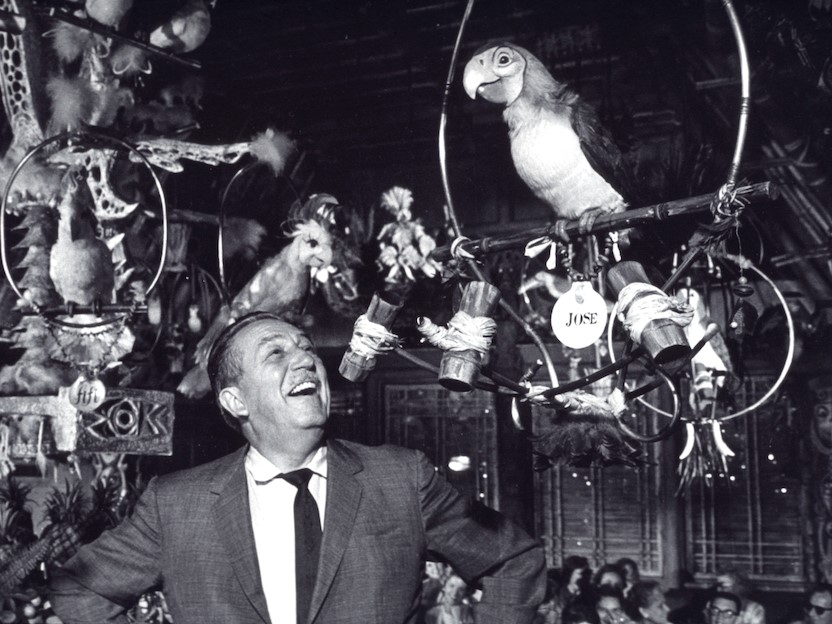

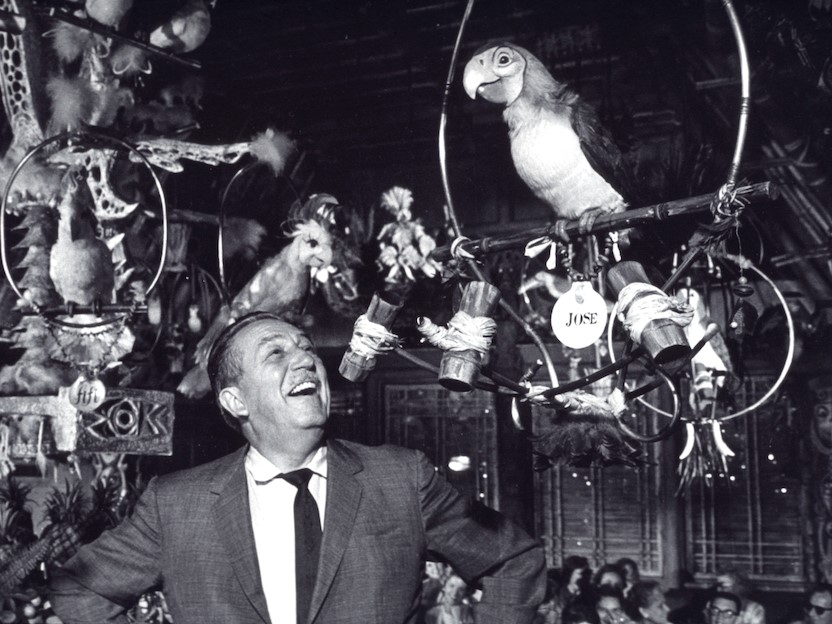

The origin story of the Walt Disney Company is as American as it gets: A (questionably racist) young entrepreneur moving across the country with nothing but his suitcase and a dream – it’s a tale as old as time in the land of opportunity. Certain backward views aside, Walt deserves credit for constantly pushing his organization forward. In its early days, Disney was known for thinking big and taking risks. The studio’s breakout film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, revolutionized the motion picture industry as the first feature-length animated movie. Subsequently, Disneyland was an absurd concept for a company that made cartoons, but the park became a smash hit because of Walt’s commitment to artistry and technological innovation. It was this bold, visionary mindset that allowed the Walt Disney Company to cement its place in popular culture.

If Disneyland was created as a celebration of American exceptionalism – portraying both a nostalgic view of the nation’s origins and a sincere belief in its future potential – today, the park is a celebration of whatever intellectual property will make the most revenue on next quarter’s financial reports. Despite this shift in priorities, Disney still represents the quintessential American business. They’re just following the lead of other large corporations which are increasingly ditching innovative thinking and risk-taking in the name of short-term profits. Consider the new initiatives coming out of Disney HQ: remakes of classic films, tiered pricing for rides, and buying back company stock. Although popular in the board room, such bland investments indicate a departure from the blue-sky philosophy that made the company a success in the first place. Thus, rather than embodying the best attributes of American entrepreneurial capitalism as it used to, Disney now exhibits some of the worst flaws.

But this isn’t just a tale of one corporation’s fall from grace. The Walt Disney Company is the Tiki Room canary in the Thunder Mountain coal mine warning us that something has gone very wrong in corporate America as a whole. Big businesses are becoming less innovative while raking in more profits – a dynamic that benefits only the shareholders of those firms. Therefore, investigating the root causes of Disney’s creative slump will reveal a fundamental flaw within the broader US economy. We could similarly ask why inequality has risen to gilded age levels, or why green technology development has been more sluggish than the humans from WALL-E. And in my opinion, the villain in each of these stories is the two-headed monster of financialization and market concentration.

Let’s address the financialization head first. A central purpose of the financial system is to extend the buying power of firms so they can make investments that will generate future profits. Consider a restaurant that wants to purchase a new oven, or a chocolate factory thinking of hiring hundreds of little people to sing songs and make candy. Paying for everything up front is not practical. That’s why loans are so crucial for keeping the economy humming along. In theory, finance should act as a facilitator of business, encouraging firms to take risks and think in the long-term. This held true in the mid-20th century when Disney was a fledgling movie studio and banking was a more modest enterprise. But after decades of incremental deregulation, our financial system has shed its traditional role and expanded to sickening proportions. The US financial sector currently accounts for 4% of employment and 8.5% of GDP but rakes in 25% of corporate profits. Shamefully, it achieved this scale by leaching off the very same companies it was meant to serve.

The rampant spread of finance is commonly referred to as “financialization”. In her book, Makers and Takers, Rana Foroohar identifies financialization as the root cause of many issues in the real economy (the part that actually makes stuff). The most publicized example of this came in 2008 when Wall Street imploded and dragged the global economy down with it. But starting even earlier, the United States has experienced decades of weak nonfinancial business investment, meaning less purchases of real assets like factories or equipment which are important drivers of growth and employment.

Source: fred.stlouisfed.org

Why is this happening? Well for one thing, contrary to its intended purpose, our mutant financial sector often discourages mature companies from investing in game-changing ideas with long-run potential. Executives listen to their shareholders and shareholders want to see steady cashflows. Therefore, public firms are incentivized to simply become maximally efficient at doing what they already do. Just look at Apple: they haven’t come up with an original product in years. In fact, evidence suggests that large firms have mostly given up on producing and applying new research.

Nowadays, decisions made in the board room are meant to please investors who prefer proven strategies over bold new ones. Maybe that’s why it’s called the “bored” room.

Even the Walt Disney Company has had its creative spark dimmed. Lately, the studio has become addicted to producing live action remakes of their classic animated films. Look up “cash-grab” in the dictionary and the accompanying image is probably a shot from The Lion King (2019). Additionally, if the Avengers Campus at Disney’s California Adventure is an indication of the quality we can expect from new additions to the parks, then it appears we’re in for a lot of cheaply themed attractions that are only handy for Instagram photos.

But the program that has theme park fans most riled up these days is Disney Genie. This new platform introduces skip-the-line fees for individual rides, turning a trip to the Magic Kingdom into even more of a pay-to-play experience than it already was.

Even the Walt Disney Company has had its creative spark dimmed. Lately, the studio has become addicted to producing live action remakes of their classic animated films. Look up “cash-grab” in the dictionary and the accompanying image is probably a shot from The Lion King (2019). Additionally, if the Avengers Campus at Disney’s California Adventure is an indication of the quality we can expect from new additions to the parks, then it appears we’re in for a lot of cheaply themed attractions that are only handy for Instagram photos.

But the program that has theme park fans most riled up these days is Disney Genie. This new platform introduces skip-the-line fees for individual rides, turning a trip to the Magic Kingdom into even more of a pay-to-play experience than it already was.

We can only speculate why the company is choosing to milk profits from their existing works rather than dream up new stories and guest experiences, although it’s safe to say that Wall Street investors are very pleased with the current trajectory. Perhaps the best indicator of where Disney’s real priorities lie is their recent series of stock buybacks. This maneuver, in which firms purchase shares of their own stock to boost the price, has become quite common in the past few decades – especially after the Trump tax cuts. With buybacks, the money spent by customers isn’t used to develop new products or pay employees; instead, earnings flow directly into the pockets of shareholders who often turn around and beg executives for fatter profit margins via cost cuts. Abagail Disney, the great-niece of Walt, took to Twitter recently to call out the company’s willingness to spend billions of dollars on share repurchases during good times and their subsequent refusal to protect workers during the pandemic.

At this point, one might ask: how can this level of laziness work as a sustainable business strategy? Remember, this is a two-headed monster we’re dealing with. Financialization is nasty enough on its own, but big companies wouldn’t be able to keep coasting off old ideas as blatantly as they do now if it wasn’t for their outsized market power.

Market concentration exists when a handful of firms produce most of the products sold in a particular market. Since the late 90s, over 75% of industries in the US have become more concentrated, leaving consumers with fewer choices in every aspect of life. To be clear, size isn’t inherently bad; having large corporations with ample resources can be helpful in certain situations (like the development of Covid vaccines). The problem is that market concentration gives companies access to various tools that would otherwise be unavailable in more competitive environments. For example, Amazon is notorious for crushing its competitors by undercutting their prices. Large companies also have the funds to simply acquire other firms. It may surprise some readers to learn that Apple didn’t develop the AI technology behind Siri. They acquired Siri, Inc – a spin-off company of the publicly funded Stanford Research Institute – to add the feature in 2010. This deal was made for R&D purposes, but many firms engage in mergers and acquisitions purely to expand their market share. If you can’t beat ‘em, eat ‘em.

This is the method favored by Disney. They don’t have a monopoly in their industry per se, but if you’re a fan of Star Wars, Marvel, or family entertainment in general, you need to pay the mouse.

Over the past two decades, the company has made several high-profile acquisitions, amassing a huge collection of intellectual properties (IP). Each of these deals represents a sort of monopoly over an existing story or character which they can use to pump out sequels or theme park attractions cashing in on people’s brand loyalty. And this brings us to the deadliest tool available to dominant firms: market power AKA monopoly power AKA the ability to price gouge. Research has shown that larger companies can lead to higher prices (the inflation we’re seeing today can be partially attributed to market concentration), and Disney is no exception. Like a gas station in the desert, Disney knows that American consumers will grudgingly accept price increases because it owns so much of the media landscape and people are attached to their brand.

Numerous studies have also identified rising market concentration as a contributing factor to the slowdown in business investment. But perhaps, as the typical justification for mergers goes, big businesses don’t need to invest as much because they are simply more efficient. This is only partly true as firms in more concentrated industries appear to achieve higher returns on their assets due to rising profit margins (price increases/ lower costs) rather than operating efficiency. If anything, the gains from scale are primarily passed on to investors. Furthermore, bigger organizations with more resources are better positioned to innovate but something is keeping them from doing so. Many are opting instead to snatch up or snuff out newer competitors. It’s no wonder that entrepreneurship is declining in the United States (except maybe on reality television) resulting in less startups that can unseat these cumbersome giants. Clearly, any improvements in efficiency stemming from market concentration should be discounted if the rest of the economy remains stagnant.

The two trends mentioned in this article are quite complex on their own, but when combined, they produce a clear result. Simply put, large corporations don’t need to try as hard to make a buck anymore. There’s no reason to invest in groundbreaking ideas when your shareholders want you to stick to the status quo and competition is nonexistent. That’s why more and more firms like Disney appear to be focused on financial engineering rather than real engineering.

Disney management has become remarkably adept at implementing sophisticated pricing schemes meant to maximize revenue per customer. Sadly, this strategy has come at the expense of some of the creative magic that was imbued by the company’s founder. So long as Disney remains unchallenged in the market for family entertainment, we will continue to see higher prices and lackluster products based on stale IP.

But corporate risk-aversion doesn’t just affect Disney fans; when every company is incentivized to underinvest and funnel cash to shareholders, inclusive economic growth becomes a fantasy on par with talking mice. Furthermore, if we ever hope to tackle significant crises like climate change, we need a dynamic private sector that is up for the challenge – poised to implement and commercialize revolutionary new technologies originated by government funded research.

To get back on the right path, there are several areas for reform. First and foremost, the wolves of Wall Street need to be neutered. I’m not qualified to offer my own solutions, so I will echo the suggestions made by Rana Foroohar in her book. Namely, the financial sector is meant to operate in service of the real economy rather than to its detriment, and to this end, regulations that aim to provide transparency and simplicity are essential. Overly risky and complex financial institutions that are “too big to fail” won’t cut it anymore. On the monopoly side, the answer is more straightforward: large corporations need to start reinvesting in our economy in a big way or face penalties. These entities owe their success to the American people as a whole – not just their shareholders. Thus, it is reasonable to expect spillover benefits to society in the form of better jobs, higher wages, or new products. Innovation must come from somewhere and we can’t keep passing the buck to Shark Tank. Hopefully, if we put finance and big business in check, we can get one step closer to reaching that great, big, beautiful tomorrow.